Research

Ramps and Ratchets: A New Paper!

This post was originally published on Nate's blog, on October 1, 2025.

This project started with a grant. My PhD advisor, Josh Bongard, specializes in evolving the designs for robots. He got funding to explore endosymbiosis: that is, making robots that operate within other robots. I found this topic fascinating, because working and evolving together is a powerful way that organisms in nature change their fate in dramatic ways. For instance: humans depend on our gut microbes to digest the foods we eat, and we would never have been able to power our big brains and live in so many diverse habitats without that collaboration.

I drew inspiration from one of my favorite biology studies, the MEGA-Plate experiment. I highly recommend you check out this two-minute video summary, but I’ll give a quick overview here. They wanted to see how new traits evolve and spread in bacterial colonies over space and time. So, they made a big rectangular habitat for E. coli, and filled the space with bands of gradually increasing amounts of antibiotic. Initially, these bands would block the bacteria from spreading, but eventually one would evolve resistance, spread into new territory, and fill it with a new lineage of slightly antibiotic resistant bacteria. This happened over and over again, gradually increasing the amount of antibiotic the bacteria could tolerate, until they reached the middle and could thrive in a brutally high dose of antibiotics that would have killed their ancestors instantly.

I love that experiment because it shows us something about antibiotics—use a big dose, and keep taking it, because too little is just an invitation for bacteria to evolve resistance—, but it also let us watch evolution unfold in real time, and showed a way to coax life into evolving some new ability, just by manipulating the environment. It got me thinking: maybe there’s something similar going on inside each of us? The gut is a habitat for bacteria, but it’s a hostile environment, one that’s meant to be selective, letting “good” bacteria survive while keeping “bad” ones out. Perhaps our gut evolved to shape how populations of bacteria spread and evolve there, guiding them towards more mutually beneficial lifestyles? I wondered, could I evolve an environment that promotes the evolution of a population inside? Could I reproduce the MEGA-Plate experiment, and maybe even evolve a better environment than what those guys designed by hand?

Actually bringing that idea to life required a lot of technical decisions. First, I had to decide what these “bacteria” would actually do. To simplify things, I chose not to simulate actual bacteria, but instead play a simple number guessing game called HIFF. Each “bacteria” is really just a number, 64 bits long when represented in binary. I kept a population of thousands of these numbers, and in each generation, I would change them one or two bits at a time, which would change the score they got in the HIFF game. It’s a hard game to win, since there are only two right answers out of 18,446,744,073,709,551,616 possible 64-bit numbers. Guesses that are closer to correct get higher scores, so the population will gradually evolve towards the right answers, but the way the scores improve is designed to be very noisy and misleading! You frequently have to get worse for a while on your way to getting better, which makes it nearly impossible for a simple Evolutionary Algorithm (EA) to solve HIFF. This seemed like a good challenge, and it was also very practical: numbers are easy for computers to work with, so I could have many thousands of them and still get results fast.

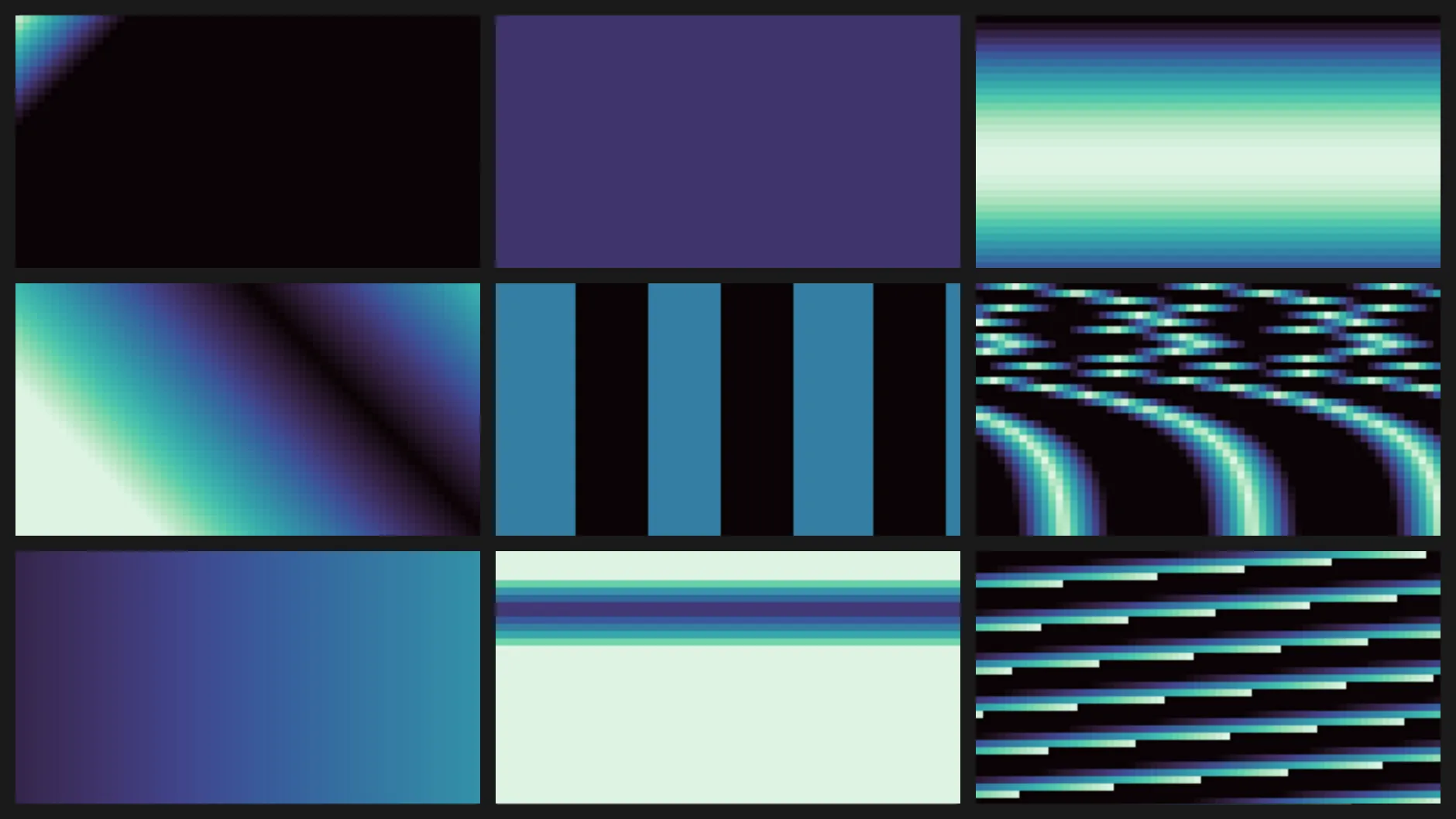

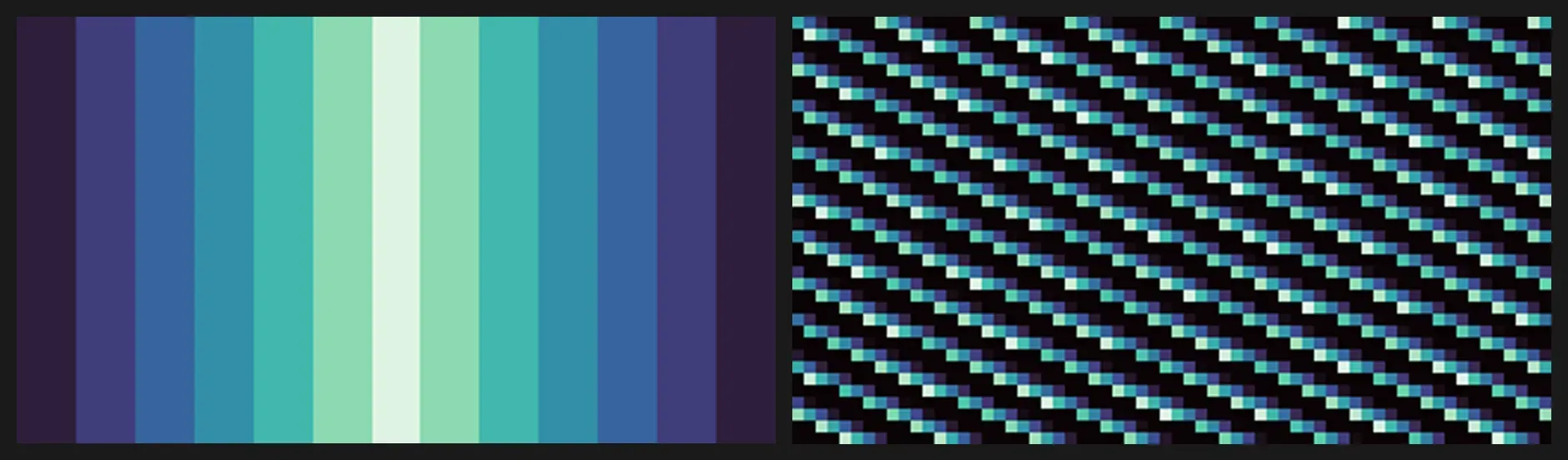

Next, I had to figure out how to put an EA into a spatial environment. Lots of people have tried that before, and in many different ways, but they almost always design the environment by hand! I couldn’t’ find any examples of someone evolving an environment like this before, which meant my idea was new, but also that I was on my own figuring out how to do it. I turned to a favorite tool of mine: Compositional Pattern Producing Networks, or CPPNs. They can make cool, organic-looking patterns with lines, curves, and smooth gradients, and that seemed like just what I wanted. Instead of laying down different amounts of antibiotics, instead I would set a minimum HIFF score needed to survive at every point on the map. Then I’d evolve those maps, keeping the ones that led the population growing inside to get higher HIFF scores.

Of course, I needed a control, too. I wanted to study how the varying difficulty levels across the environment affected evolution, so one obvious comparison was a flat environment, with no minimum score at all. I also tried a version of the MEGA-Plate experiment design, since that seemed to work so well in real life. It took a lot of tinkering to get it working, and frustratingly it only seemed to work under just the right conditions, but eventually I got results that looked like the bacteria in that video. Even more exciting, I could evolve environments to do the same thing.

The concept worked! But, how? And why did it need to be set up in such a particular way? It felt like only a partial success. What did it mean, and why should anyone care? It wasn’t clear at first, but I decided to stick with it. I read a lot of past research about the factors that might be at play here, drawing on both computer science and biology. I also spent a long time staring at the results and tweaking things to see what would happen.

The clue that really made things click for me was when I did a “hyperparameter sweep.” Originally, I found that the MEGA-Plate copycat beat out the flat environment, but only when I configured the EA juuuuust right. In other cases, the flat environment did just as well or even a bit better. Claiming “success” felt a bit like cheating. So, I decided to try all the possible settings, to see precisely where it did better. Turns out, the key factor was selection pressure. When I made it so that numbers with higher scores could reproduce faster, then evolution worked just fine in any of my environments. But when I didn’t do that, when I let any number survive as long as it was “good enough,” with no particular edge over its neighbors, then the more challenging environments paradoxically produced better HIFF scores. After a few more tests, I convinced myself: somehow the spatial structure of the environment was inducing selection pressure, without me having to explicitly program it into the algorithm.

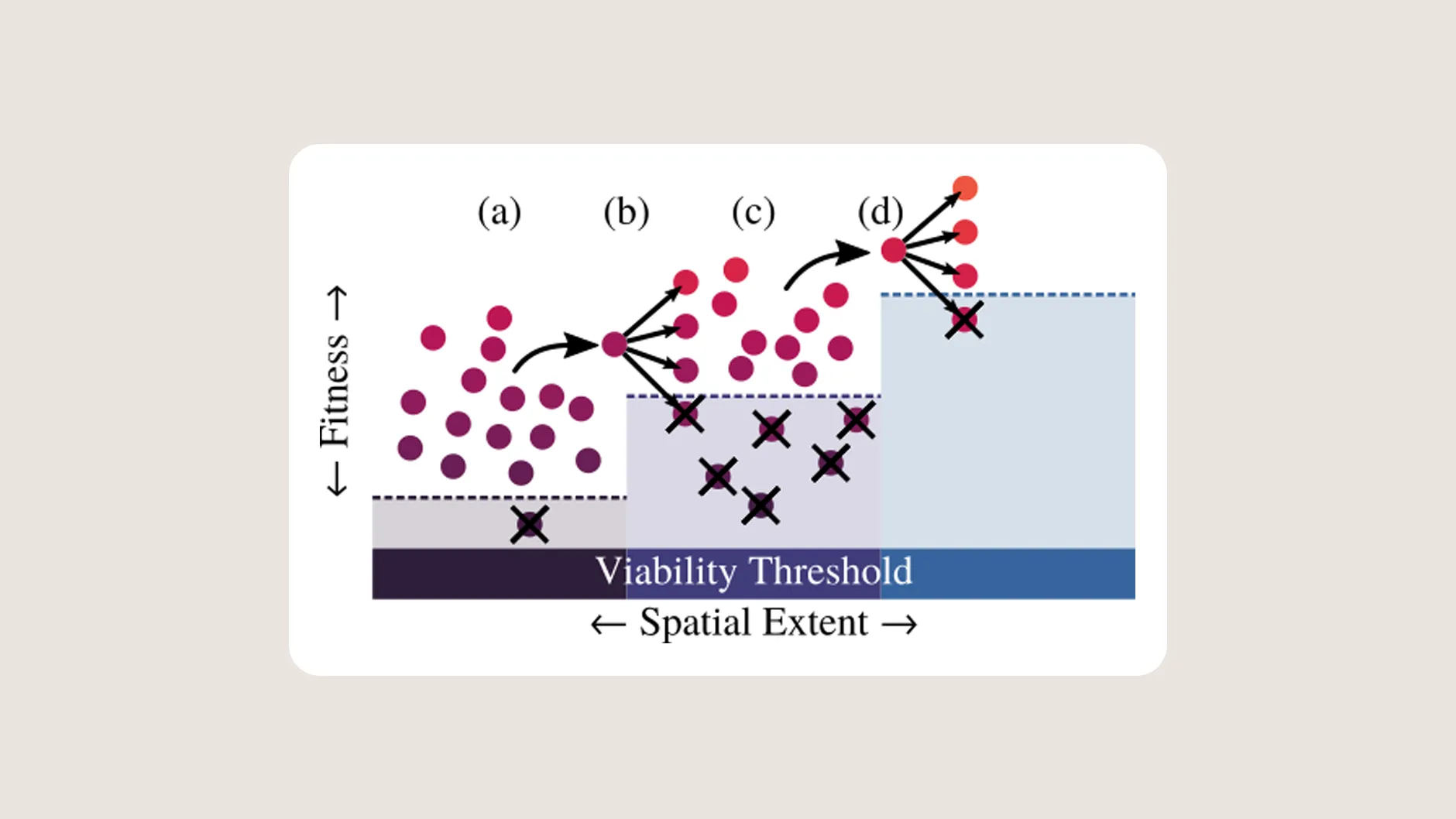

I think the way this works is fascinating. When I first lay down the “bacteria” into my simulated MEGA-Plate environment, most of them die right away! They simply can’t survive in the toxic middle area, and so they die out and leave empty space behind. The ones lucky enough to be placed near the edges, though, they do fine. They keep evolving, gradually getting better HIFF scores. Eventually, one of them gets a high enough score that it can survive in the next space over, so it migrates there and finds itself alone in a big open space. Since it has no competition, it gets to reproduce like crazy, completely filling the new territory with its children, each one just a little bit different from itself, because of mutations. Except, the minimum score here is a bit higher than before. Any children that get a much lower score can’t survive here; only the ones that are about the same or better can. That means the environment works like a ratchet, pushing the population to ever high scores as they gradually climb the ramp of increasing difficulty.

Looking at it another way, my algorithm starts out by broadly exploring the space of possible numbers, without concern for which ones are better or worse. But, when one does get a higher score, that one gets rewarded with access to more territory and more children. That’s like starting up a whole new evolutionary search, beginning from a better baseline. When that happens, I go back to searching very broadly, just with a higher standard for survival. Any number is allowed, just so long as it isn’t worse. The spatial structure of the environment and its gradual ramp up in difficulty is what decides how strong the selection pressure is, and what manages this back-and-forth process of “exploring” the search space very broadly and “exploiting” the numbers that got higher scores. This “explore / exploit trade-off” is a big topic of interest in the field of EAs, and something we typically have to tune by hand, but I got an EA to automatically solve this problem for me!

It’s still not clear how to make this practically useful. HIFF is just a number guessing game that I used it as a stand-in for some more interesting task. This kind of EA ought to be good at open-ended exploration of complex problems, which is why it does well at a deceptive problem, like HIFF. But HIFF only has two best answers! This approach might be much more useful and interesting in a more open-ended problem area, where there are countless different ways to succeed. Perhaps something like a robot, or a game-playing AI, or a search for many good answers, rather than the best answer. But I won’t know until I actually try!

Overall, I’m quite happy with this experiment. I was able to reproduce results from a favorite biology paper on my computer, and show how it relates to the kinds of search and optimization problems that Computer Scientists care about. I also got to apply the CS perspective to a Biology experiment, analyzing this “range expansion” phenomenon in terms of problem solving and search processes. It’s a modest start, but this is exactly the kind of work I set out to do, and I had a lot of fun doing it. It also earned an A+ for me and my partner, Anna Rees, on our final project for Evolutionary Computation class, a trip to Japan, and even a nomination for best paper at ALife 2025! So that’s pretty sweet. I hope to do more like this in the future.